How are you spending your days during stay-at-home?

I expanded my medicinal plant garden right when COVID lockdowns began, and also started to grow some food plants, although most of them lean toward sacred plants (they are often both!). I am gardening, cleaning, reading, exercising, and working in the studio, when I am doing anything. I also pass a lot of time with plants, playing in various modalities of sentience and consciousness. I am trying to be patient with thinking as new ideas run the gauntlet of conviction and possibility. This process of suspended time for me isn’t that unusual, just perhaps a bit exaggerated now. I am developing some new techniques for casting and building, which provide some degree of material/physical satisfaction, as does planning new forms.

Studio visits and garden visits with friends break up the endless self-reflexive wheel of the cyclical thought trap or the “groundhog day” redundancy of having no horizon line, floating in the ether or the bardo of this stretch of time. I would like to have more concrete future plans, but without those, I’m finding myself relaxing into the uncertainty at times and finding some solitude.

Estaciones, 2017/19, steel, copper, silicone, wool, pigment, 14 x 18 x 18 in (35.6 x 45.7 x 45.7 cm) steel parts

How has this impacted work?

I love my work completely and it brings me great joy and excitement when I am engaged fully in it. As well as for all workers, now is a scary time for artists, though, all of us. The exaggerated isolation coupled with material uncertainty presents difficulties with morale as well as in the logistical world of resourcing, planning, and making—let alone presenting. If you’re worried about food and where to live it’s hard to make work, definitely harder than any of those “precedented” times. The COVID roulette wheel is spinning.

I spend a lot of unstructured time alone in the studio, reading, drawing, and thinking anyway so “isolation” is more of the same except without group events and with no time horizon, and missing my people and places more than usual. Out of necessity, this time has facilitated a deep dive into dream states and content of the subconscious, which drives new ideas for work and connects me to my roots in the world, unwinding and reconnecting with the complex narratives that form our identities, the plasticity of memory, experiences, geographies, and textures. There’s a lot of mysterious information held in our bodies that can leak out now and again. I am listening in case something important comes through. I like to think it is coming through, because this exploration makes me feel very comfortable in the world: at home with myself and deeply connected to the rest of humanity.

David Hammons, African-American Flag, 1990, dyed cotton, ©DAVID HAMMONS/COURTESY THE BROAD ART FOUNDATION.

Is there an artwork that currently resonates with you at this moment and why?

David Hammons “African American Flag”. I have been a fan of his practice since I first saw his 1992 “Untitled” hair piece as a teenager. His conversation moves within and beyond symbolism to weave a narrative across time, between the viewer and the material, and takes it into spiritual realms. There’s such a polished and raw quality to the material of the pieces that speaks a bare emotional truth and communicates urgently, they are stunning. So I’m thinking a lot about his pieces—like his “Untitled” bottle wheel piece from 1989, for example. I’ve thought often of the simplicity and perfection of that work since I first saw it like 20-something years ago. I’m happy to see his work becoming more popularly known among wider audiences beyond contemporary art, I now see it often online on social media, in support of Black Lives Matter, in particular, his “African American Flag”, and the sheer the power and necessity of that work.

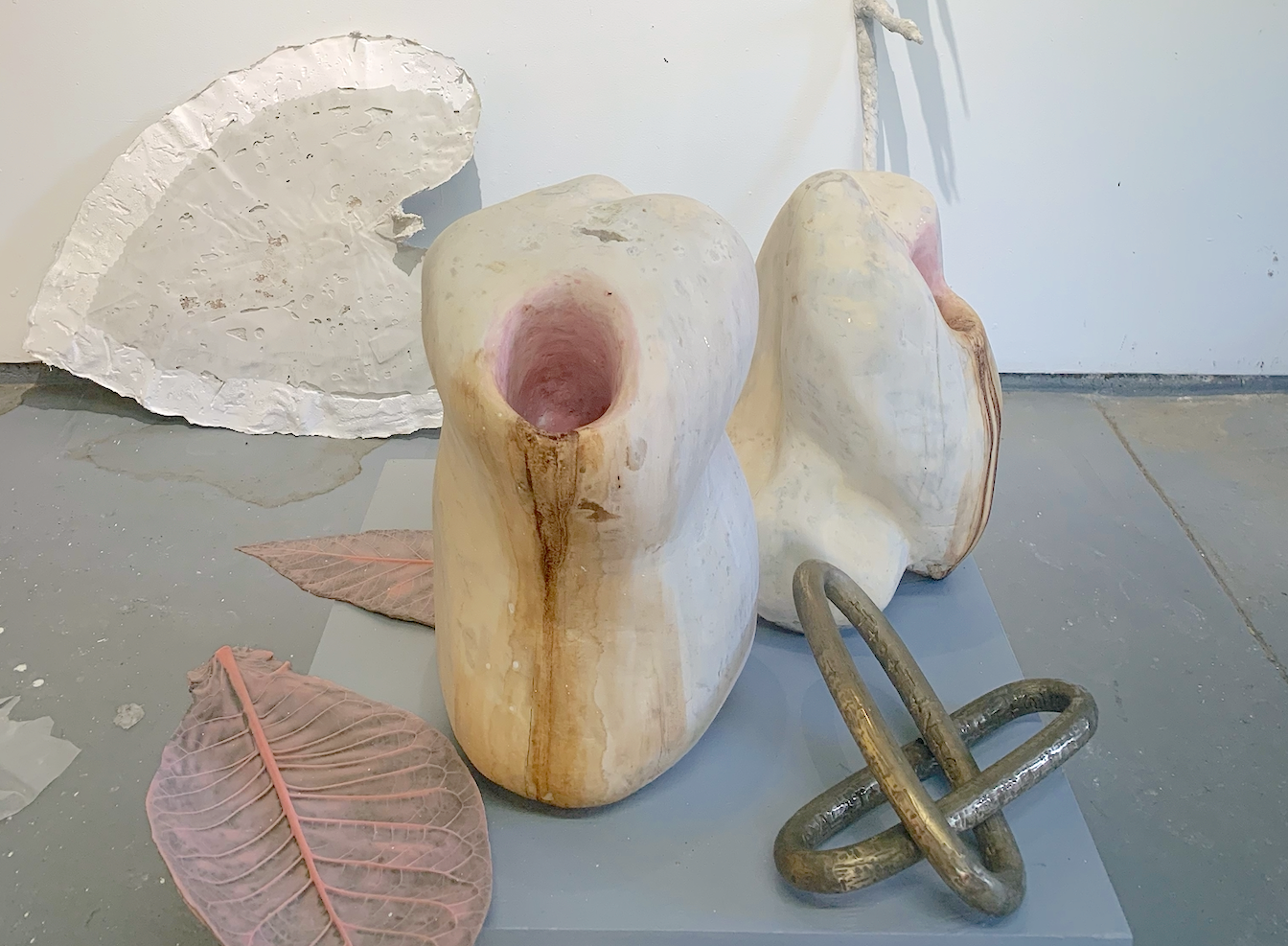

Karen Lofgren, Studio View, Los Angeles, CA.

For the last two years you have been working on a series that builds upon your research into the history of ritual healing and belief in ancient plant medicine, themes that are pertinent to the current global pandemic, do you feel this series has taken on a new connotation?

I have been working on pieces about these subjects, about the rise and fall of cultures, about encroachment and destruction of the natural world, how we as humans interact with other wild systems, and natural defense systems for the past number of years. I had been wondering how we are so sick as a culture and how we might move toward healing as a species. I was/am studying older western ritual medicine as well as various forms of ancient Indigenous medicine, looking at various approaches to being part of the natural world, embodied spaces, and sentience in non-human species. I became most curious about plant dialogue and plant sentience, and global animist traditions, which, I believe, rightly regard all species as sentient—as well as real chemistry between species—as we see in shamanism and pharmacology—employing alkaloids and other naturally-occurring compounds to alter the chemistry of non-plant bodies. There are more cures for curses in ancient medicine than almost any other thing, so those cures and rites intrigued me. If we used them for thousands of years, perhaps there is a reason for that. What if they worked?

Installation View of ‘Brave New Worlds’, Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs, CA.

In series like Pulling Through, a softer index, I made objects that were intended to transfer disease, to create portals for magical or symbolic rebirth, while tracing the scale and movements of human bodies performing healing rituals, the final forms also trying to propose new “soft” indexing systems that leave room for questions looking at human cultural systems and other wild systems, and the activation of belief. The pieces were based initially on healing rituals practiced for some thousands of years called “pulling through” or “passing through” that I found in texts about folk medicine practices. Belief plays a big role in the body’s response to medicine, so it is likely that cures for curses could actually work.

DEFENDER #4, 2018, epoxy, wool, acrylic, pigeon spikes, 34 x 2 x 4.5 in (86.4 x 5.1 x 11.4 cm)

I am also a couple years into making a series called DEFENDERS (begun in 2017) about invasive species and colonialism—using pigeon evasion spikes to create viral-looking elongated cast resin forms. These forms helped me to think about self-defense mechanisms of the earth or of the natural world, a type of horror-femme violence toward self-preservation—forms first inspired by the devastatingly beautiful and deadly toxic caterpillars in the Amazon rainforest, where I lived for a time. In terms of topicality in popular culture, the subjects seem to be all coming up and fast. It’s an interesting ride and I am continuing in the work.

Sometimes people forget we are nature because we focus so much on our own species and forget the millions of others. We are nature, and COVID is also nature. The violence of our species and the plundering of mother earth in service to extreme capitalist greed has got us to where we are: practicing daily ritual sacrifice toward mass extinction. We are a very young species and there’s just so much we don’t know.

Karen Lofgren, Studio View, Los Angeles, CA.

What do you imagine for the future of the art community and world at large as we rebuild together?

We need each other, most of all, to find out over and over how to “stay alive and continue and not die” as Philip Guston put it, and the entire setup of our lives seems always fragile, changing, and reshaping. There will always be artists making work and trying to find new forms, new contexts, and scopes, and finding platforms to share this work in public spaces. We can’t know what support systems might be available in the future so we have to try to figure out how to continue and not die for now. We need to feel part of a larger dialogue with the world to continue to build our end of it, I think a lot of us do, we need culture, it is vital, it’s our reason, the beauty of our species. We will find new ways, together, in time. Right now we are in a triage phase. We definitely must keep making and sharing, which are the generative acts that define our species in the most positive way. Focusing on our strengths. Love is a strength, and our great love for other makers and thinkers is a strength. Our capacity to collaborate and form communities is a strength. Curiosity and openness are strengths. This is culture and it’s the best part of us.

I don’t know yet what role sculpture has on our landscape in the near future but I think it has to have a place—it always has had, at least the past 40,000 years or so. It’s probably not going anywhere. That said, a lot of artists, along with all workers, are in real trouble right now. We need to find new ways to expand cultural dialogue beyond traditional means of production and exhibition, as well as to develop new types of support systems or possibilities for patronage so that we can continue.